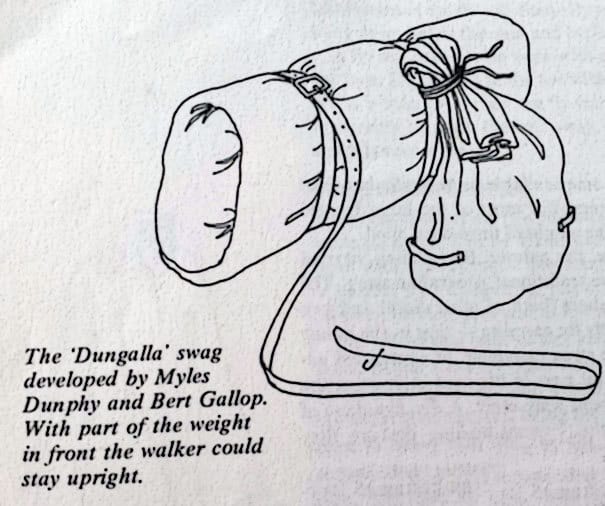

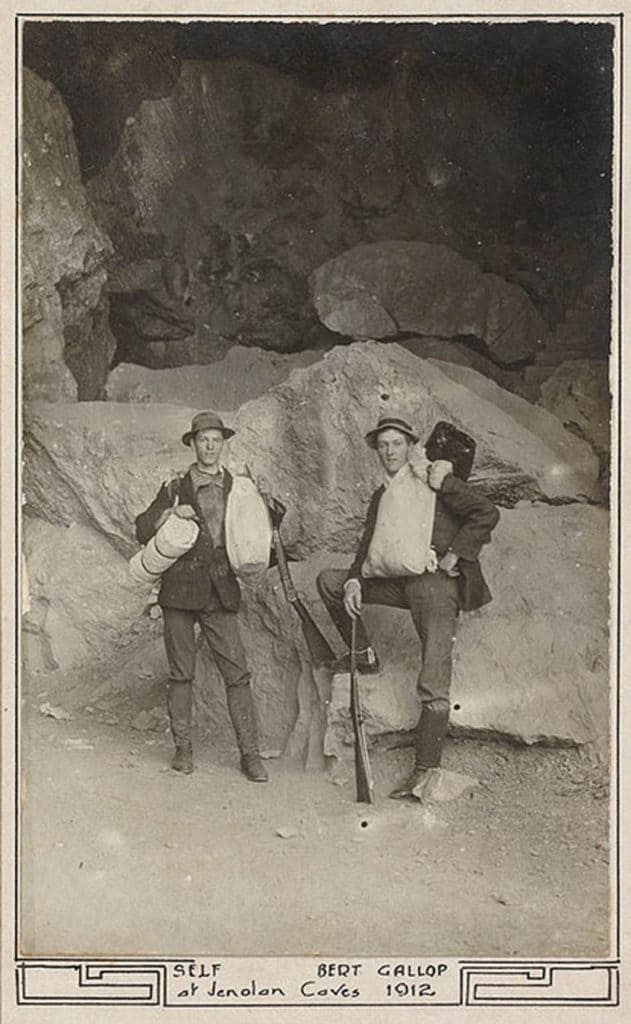

A swag may be the best way to carry your hiking gear. Grandma Gatewood did, and so have thousands of others: Much of this post comes from Richard Graves, Australian Bushcraft: ‘The swag (or ‘bluey’) is the proverbial means of carrying a load and it is one of the best methods in existence. It has the advantage of being extremely well balanced, two-thirds of the weight being carried behind the body and about one-third in front. The result of this balance is that the carrier walks completely upright: Clothes, tent, bedding and the gear not wanted for the day’s walk are carried in the swag at the back, while the food and cooking utensils and the day’s needs are in the ‘dilly’ bag in front. Because of this the swag is not opened during the day but the dilly bag attached to the front is immediately accessible.

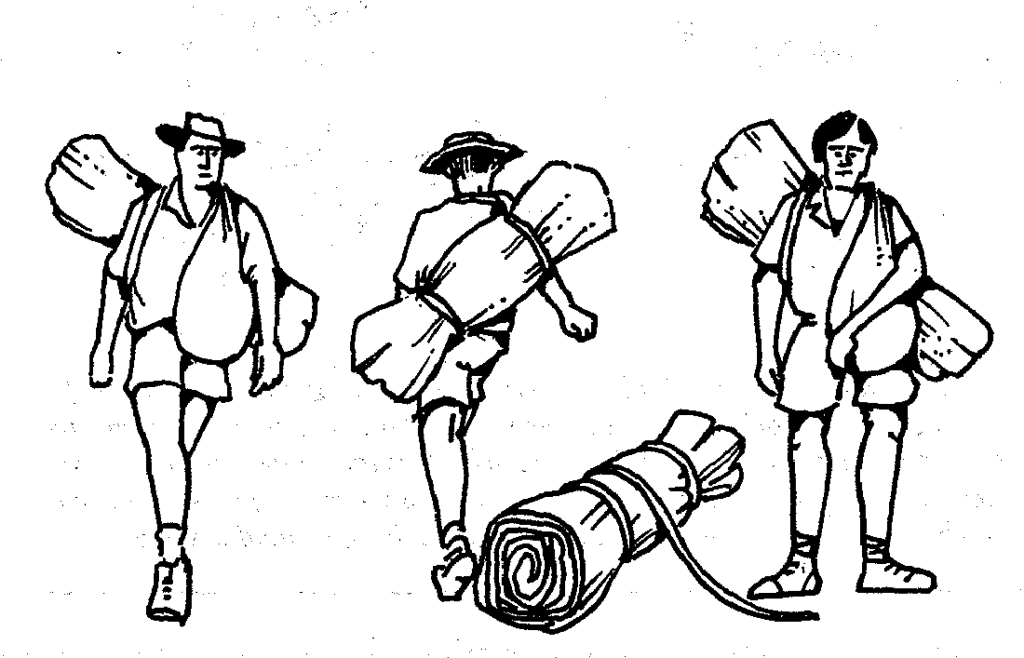

The only materials necessary to make a swag are a strap, two binding straps and the dilly bag. The swag strap, preferably of soft leather or light webbing, should be about 1 metre long and about 5 cm or more wide. The two binding strips The rolled swag, containing bedding and other gear, is carried on the back while the dilly bag, containing the day’s needs, is carried on the front.

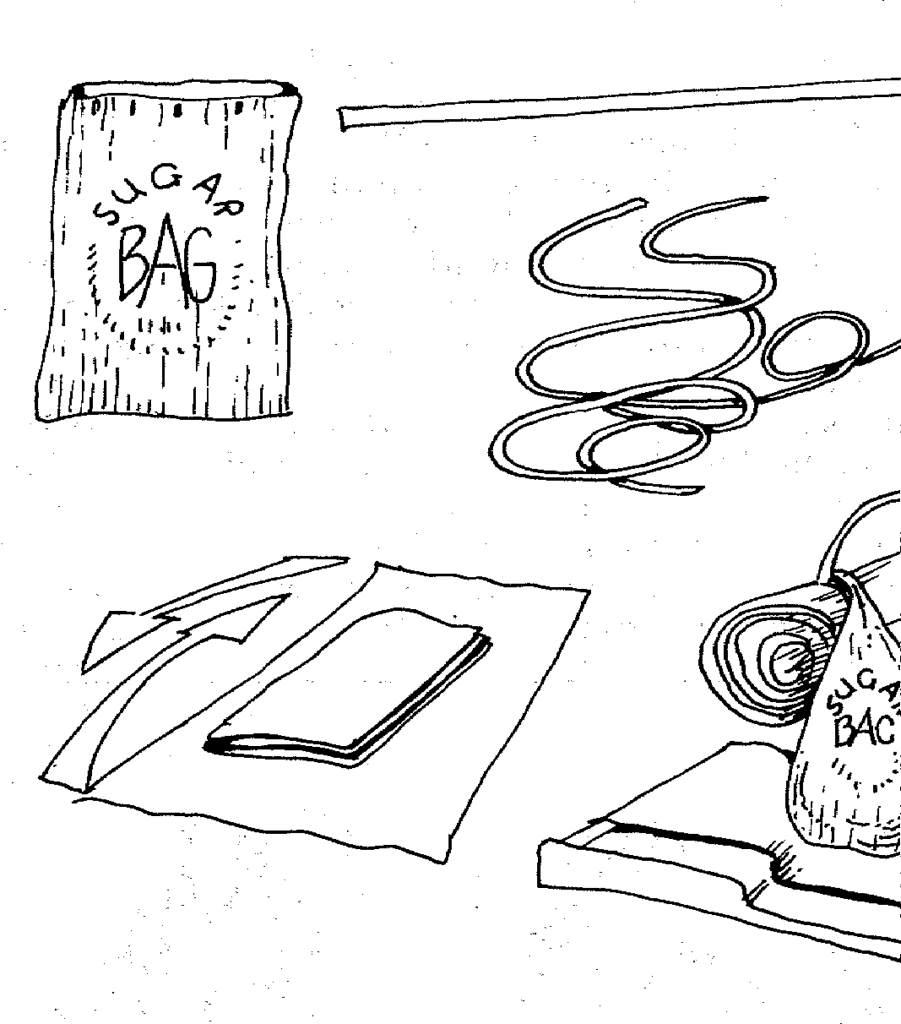

The swag is Australia’s oldest method of carrying things on foot as far as bush workers were concerned. Although it now has been displaced by many imported and fancy packs it remains one ofthe most practical means of ‘backpacking’ bedding and food over long tramps on relatively flat country. The construction and packing method is shown. The strap can be of any material such as plaited cord or rope. Traditionally the dilly bag was an old sugar or flour sack, but a nylon weatherproof bag that allows some breathing (because it is also used to contain the day’s rations) can be of any convenient shape and size.

Half the knack of carrying a swag consists in knowing how to swing it. Lay the roll, with the dilly bag extended, in front of you. Put the arm farthest away from the dilly bag through the swag strap. Heave the roll towards your back and swing the body towards the swag, so that the dilly bag flies up and out. Duck the opposite shoulder and catch the dilly bag on it. The strap will then lie over one shoulder and the dilly bag over the other with the swag roll carried at an angle across the back.

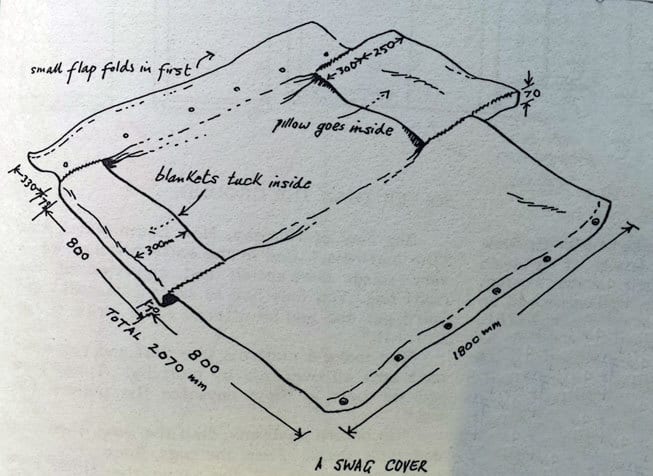

Ron Edwards Swag Pattern:

An alternative method of carrying the swag is to use two straps, one about 1 metre long and the other about 2 metres. Both straps should be about 3 cm wide and made of strong material, although it should be soft. The roll is made for the swag and the long strap tied securely about 15 cm from one end of the roll. Fifteen cm from the other end of the roll the other strap is fastened, with the dilly bag held in position by this binding. The swag is lifted to the left shoulder with the dilly bag in front and the roll at the back, the neck of the dilly bag hanging over the left shoulder. The long strap is passed on top of the right shoulder and then under the armpit and around the back. Then it is tied to a loop at the bottom corner of the dilly bag. This type of swag prevents the dilly bag from swaying.

To pack and roll the swag itself, lay your groundsheet or swag cover (traditionally a blanket) on the ground and then fold your other blankets to a width of about 80 cm. Lay spare clothes lengthways on top with your other gear. Fold in the sides of the groundsheet and roll the whole from the blanket end to the free side so that it is tight. If a tent is being carried, this ‘inner swag’ is then rolled in it. The two binding cords are passed through the swag strap to stop slipping. The dilly bag is then attached to one of the binding straps at its junction with the swag strap.’

To pack and roll the swag itself, lay your groundsheet or swag cover (traditionally a blanket) on the ground and then fold your other blankets to a width of about 80 cm. Lay spare clothes lengthways on top with your other gear. Fold in the sides of the groundsheet and roll the whole from the blanket end to the free side so that it is tight. If a tent is being carried, this ‘inner swag’ is then rolled in it. The two binding cords are passed through the swag strap to stop slipping. The dilly bag is then attached to one of the binding straps at its junction with the swag strap.’

Miles Dunphy:

Recommended reading: Diary of a Welsh Swagman, Joseph Jenkins: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Jenkins

A couple of poems about swagmen will not go awry:

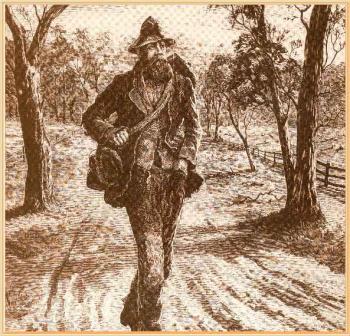

The Swagman

C.J. Dennis

His bushy whiskers and his hair

Were all fussed up and very grey

He said he’d come a long, long way

And had a long, long way to go.

Each boot was broken at the toe,

And he’d a swag upon his back.

His billy-can, as black as black,

Was just the thing for making tea

At picnics, so it seemed to me.’Twas hard to earn a bite of bread,

He told me. Then he shook his head,

And all the little corks that hung

Around his hat-brim danced and swung

And bobbed about his face; and when

I laughed he made them dance again.

He said they were for keeping flies –

“The pesky varmints” – from his eyes.

He called me “Codger”. . . “Now you see

The best days of your life,” said he.

“But days will come to bend your back,

And, when they come, keep off the track.

Keep off, young codger, if you can.

He seemed a funny sort of man.He told me that he wanted work,

But jobs were scarce this side of Bourke,

And he supposed he’d have to go

Another fifty mile or so.

“Nigh all my life the track I’ve walked,”

He said. I liked the way he talked.

And oh, the places he had seen!

I don’t know where he had not been –

On every road, in every town,

All through the country, up and down.

“Young codger, shun the track,” he said.

And put his hand upon my head.

I noticed, then, that his old eyes

Were very blue and very wise.

“Ay, once I was a little lad,”

He said, and seemed to grow quite sad.I sometimes think: When I’m a man,

I’ll get a good black billy-can

And hang some corks around my hat,

And lead a jolly life like that.

Waltzing Matilda

Banjo Paterson & Christina MacPherson

Once a jolly swagman camped by a billabong

Under the shade of a coolibah tree,

He sang as he watched and waited ’til his billy boiled

You’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me

Waltzing Matilda, Waltzing Matilda

You’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me

He sang as he watched and waited ’til his billy boiled,

you’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me

Down came a jumbuck to drink at the billabong,

Up jumped the swagman and grabbed him with glee,

he sang as he shoved that jumbuck in his tucker bag,

you’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me

Waltzing Matilda, Waltzing Matilda

you’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me

he sang as he shoved that jumbuck in his tucker bag,

You’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me

Up rode the squatter, mounted on his thoroughbred,

Up rode the troopers, one, two, three,

With the jolly jumbuck you’ve got in your tucker bag?

You’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me.

Waltzing Matilda, Waltzing Matilda

You’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me

With the jolly jumbuck you’ve got in your tucker bag?

You’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, you scoundrel with me.

Up jumped the swagman and sprang into the billabong,

You’ll never catch me alive, said he,

And his ghost may be heard as you pass by that billabong,

you’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me.

Waltzing Matilda, Waltzing Matilda

You’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me

his ghost may be heard as you pass by that billabong,

You’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me.

Oh, you’ll come a-Waltzing Matilda, with me.

13/11/2016: Deconstructing Waltzing Matilda, Australia’s Favourite Song

Waltzing Matilda is an Australian icon. It is quite likely that more Australians know the words to this song than even their national anthem. There is probably no other song that is more easily recognised by a populace: young or old: native or a newly arrived immigrant.

The lyrics to Waltzing Matilda were (allegedly) written in 1895 by Banjo Paterson, an Australian bush poet, while holidaying on a huge cattle and sheep station (ranch) in the Australian Outback. He was inspired by a tune he heard being played by Christina Macpherson the daughter of the owner of the property. Banjo and Christina worked together composing the song. Whether they also got it away is left to your imagination. She set the music for Waltzing Matilda. The song was an instant hit. The words were written to a tune played on a zither or autoharp by 31‑year‑old Christina, one of the family members at the station. 31? Old for such high jinks!

Macpherson had heard the tune ‘The Craigielee March’ played by a military band while attending the Warrnambool steeplechase horse racing in Victoria in April 1894, and played it back by ear at Dagworth. Paterson decided that the music would be a good piece to set lyrics to, and produced the original version during the rest of his stay at the station and in Winton.

As with so many icons of the Left, there is a degree of dishonesty at its heart. For example, the tune was stolen: The march was based on the Scottish Celtic folk tune ‘Thou Bonnie Wood of Craigielea’, written by Robert Tannahill and first published in 1806, with James Barr composing the music in 1818. In the early 1890s it was arranged as the ‘The Craigielee’ march music for brass band by Thomas Bulch. This tune, in turn, was possibly based on the old melody of ‘Go to the Devil and Shake Yourself’ (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xO1DPWLumvw), composed by John Field (1782–1837) sometime before 1812. Banjo’s song was first recorded by John Collinson in 1926. You can listen to it here: http://aso.gov.au/titles/music/waltzing-matilda/clip1/ I think I prefer the original title, ‘Go to the Devil and Shake Yourself’!

Of course Paterson composed the song in what was to be the birthplace of Australia’s Left (Australian Labor Party = Barcaldine) just after the great ‘Shearer’s Strike’ of 1891 (itself a consequence more of the 1890’s (climate change) drought than anything else, and the founding of the unsuccessful ‘New Australia’ in Paraguay (by the disgruntled leftist insurgents 1892). All these things are connected, and connected to the Australian leftist (ortho) doxy! One day their history will be written, but not be me! In 1890 Bourke was a centre of ‘culture’ (if you can call anything the left touches ‘culture’), had a grand opera house, was a centre of ‘civilisation’ and a magnet for the literati. It was no accident Paterson was there. Today it is a hell hole (after a century of leftist social experimentation) with the highest crime rate of anywhere on the planet, for example. Interesting aside: In the Western Lands Lease country (West of the Darling) in the 1880s you could milk a cow on four acres. There were substantial towns all over the place and 100,000 folk lived there. The ‘New Australia’ movement wanted to secede and form their own socialist paradise there. It had to be abandoned as a result of the 1890s drought (that’s why they went to Paraguay https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Australia) and never recovered. No-one at all lives there today! I suspect a leftist future is no different from a leftist past!

First read the song Waltzing Matilda (below) again , then I will begin to ‘decontruct’ it for you:

Waltzing Matilda, Lyrics to Song

1Once a jolly swagman camped by a billabong

2Under the shade of a coolibah tree

3And he sang as he watched and waited ’til his billy boiled

4Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me?

5Waltzing Matilda, Waltzing Matilda

6Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me

7And he sang as he watched and waited ’til his billy boiled

8Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me?

9Along came a jumbuck to drink at the billabong

10Up jumped the swagman and grabbed him with glee

11And he sang as he stowed that jumbuck in his tucker bag

12You’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me.

13Waltzing Matilda, Waltzing Matilda

14Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me

15And he sang as he watched and waited ’til his billy boiled

16Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me?

17Up rode the squatter, mounted on his thoroughbred

18Down came the troopers, one, two, three

19Whose is that jumbuck you’ve got in your tucker bag?

20You’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me.

21Waltzing Matilda, Waltzing Matilda

22Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me

23And he sang as he watched and waited ’til his billy boiled

24Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me?

25Up jumped the swagman, leapt into the billabong,

26You’ll never catch me alive, said he

27And his ghost may be heard as you pass by the billabong

28Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me.

29Waltzing Matilda, Waltzing Matilda

30Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me

31And he sang as he watched and waited ’til his billy boiled

32Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me?

Just some key words: First ‘camped’ (Line 1) rather than ‘trespassed’. This innocuous word sets the scene for who is in the right and who in the wrong in this interchange of ideas and clash of social classes. The swagman is innocently ‘camping’ amid a benevolent nature which will provide him with all its largesse (food, drink peace) as his ‘right’. The tranquillity and ‘appropriateness’ of the scene is emphasized over and over again by the choice of words ‘waltzing’ and ‘singing’ for example (Lines 11,12,13,14,15,16!). There is no indication that he is a ruffian who has no business being where he is. In reality the swagman is a shiftless idle derelict, illegally trespassing on someone else’s private property which the owner has paid good money for and spent considerable effort and work building up, eg creating mobs of (highly edible) sheep, which the swagman wantonly kills and steals.

The ‘class’ difference between the protagonists (and the role of the Government in reinforcing this class system) is emphasized by the choice of word to describe them their conveyances and possessions. The swagman is on foot (‘waltzing) whereas the owner (described disphemistically) as a ‘squatter’ (as if he had no right to the land -though he had actually paid for it!) is ‘mounted’ (to stress his ‘

High falutin’ nature, and not just on any common nag (it would in reality have been a ‘whaler’) but on a ‘thoroughbred’ (which would in fact have been little use for mustering sheep – it would break its legs!) His actions are backed up by the full force of the establishment and the law by the presence of not just one but by a whole bevy of gendarmes (three) so that at the outset the ‘poor’ swagman is outnumbered (four to one) by the onerous forces of capital and the law – O, the injustice of it all!

Of course the poem was written in response to the Great Shearer’s Strike (it became almost a civil war) and led to many gaolings and deaths, and the burning of many shearing sheds – and also to the founding of the ‘New Australia’ colony in Paraguay and incidentally to the founding of the Labor Party, not far from where it was written – by just such leftists as Paterson. In those days Bourke was a centre of culture. Many people wanted to form a socialist republic West of the Darling where 100,000 people dwelt then (but no-one does today- after the drought of 1890 failed to go away – climate change!) Today Bourke has the highest crime rate in the world!

Let’s look at how that crime is dealt with: The ‘jumbuck’ (‘sheep’ = Line 9) is obviously innocently coming to the stream for its evening drink when the swagman ‘grabs’ him and ‘stows’ him. The violence of this encounter is glossed over and the swagman places the remains of the sheep in his food bag as if it were his own property. There is no hint in the song though of ‘blood upon the wattle’. There is no indication even that the action was ‘unkind’. The sheep might almost later on extricate itself from the offending bag after having had a peaceful nap, and saunter on its way as if the whole episode had been a friendly jape! Performed after all, with ‘glee’. I’m not sure however if the wether appreciated the jest! He is a bloody mess of meat after all, hacked to pieces. It is astonishing to what an extent the passivity of the crime is glossed over. The swagman just ‘watches and waits’; it is the squatter and his troopers who are the actors. They ‘ride up’ and ‘come down’, etc.

The squatter at least comes straight to the point, ‘Whose is that jumbuck’? He says. Every event in Australia’s history revolves around how you answer this question. We all are supposed to ‘know’ surely by now (the Labor Party and the Trade Unions have told us often enough) that the ‘bosses’ have (mis) appropriated all the world’s wealth for their own nefarious purposes, holding the rest of us in an impecunious subjugation which will not even end with our deaths. ‘You’ll never catch me alive’ sings the swagman and ‘jumps into the billabong.’ He almost certainly needed a good bath anyway having been an indigent derelict sleeping rough for some time and no doubt carefully boiling methylated spirits (or the ‘White Lady – I know you imagined ‘tea’ – such innocence) in that billy anyway, a foul habit which can often also lead to incontinence and madness – which it clearly has in this case!

It was clearly quite mad to drown yourself simply over the theft of some mutton anyway, a crime which would most likely only have met with a small fine in those days. If this event is supposed to have taken place before Samuel Mort invented refrigerated transport (c1883 and therefore likely – Now Elders incidentally), then you should know that meat was practically free up until then as the only usable products of the grazing industry were tallow (fat), hides and wool as anyone who has played the board game ‘Squatter’, an Australian version of ‘Monopoly’ ought to know. Meat was simply a waste product. At one time for example they used to tip up to 4 million sheep carcasses into the Murray at Echuca annually (after rendering). The smell (and environmental consequences) are hard to imagine. One thing though; it did lead to the development of the largest Murray Cod in history (bigger than a man!), and indeed to an inland fisheries industry, now sadly defunct!

You will note that the cops (troopers) do nothing. Just like cops of every age, they are just in it for the take, eg their fat horses. They do nothing to prevent crime or to solve it.

I also like the morsel of moral advice that you should ‘pass by this billabong’. Its pollution by dead swagmen and sheep is bad enough. I think there is also the suggestion that ‘you’ should eschew a like fate. Whether this means you should desist from rustling, drinking meths, bathing, having anything to do with the police or etc is left to your own imagination – as it should be!

The constant refrain ‘Who’ll’? and its answering chorus, ‘You’ll’ is just too obvious to require explanation. If you have been sucked in by leftist gibberish, no doubt you are totally ignorant and might as well be off ‘waltzing matilda’ with the fairies or lying somewhere (dare I say ‘unlamented’?) on the bottom of some Billabong or other suitable receptacle for the disposal of dead bodies!

The swagman will have his revenge. We are doomed to be haunted by his ghost – just as we are haunted by the ghosts of Whitlam and Keating! Wait a moment! Keating is not dead. He just always looks dead. His is the undead hand of capitalism! Or socialism. Well, something like that.

It would be interesting to test this approach against modern gear.

Go for it.