‘It is no trouble to light a fire with a large magnifying glass when the sun is shining in a clear sky, but it is a different matter if the lens is small or if only brief, occasional gleams of sun come through gaps in the clouds. It can be done quite easily, however, by taking into account elementary physics. White or light-coloured surfaces reflect heat, so with a very small lens or under poor conditions it is useless to try to light a piece of paper, a leaf, or dry grass. But black absorbs heat and therein lies the whole secret of success.

This can be demonstrated in a striking way by using a prospector’s lens, no larger than a 2-cent piece, or the almost as small eyepiece from .a pocket telescope or pair of binoculars. Wait until the lower rim of the sun is just touching the horizon—the time when least heat is received from it—and then focus the rays on a piece of black tinder made from cotton cloth. Within 2 or 3 seconds the tinder will start to glow. The same thing happens when the sun gleams for a second or two through a gap in driving clouds.

If no tinder is available, use a tiny ball of cotton thread taken from the clothing, or some very fine threads of grass leaf or inner fibrous bark, bone dry and blackened by thorough rubbing between the finger and thumb with a scrap of old, soft charcoal.

Lighting a “fire in wet weather is another art which must be mastered. The worst conditions are those under which so many of our troops lived, ate, slept, fought, and died in the jungles of New Guinea. Through the steamy green gloom of the rain forest the tall columns of the trees rise to a thick ceiling of leaves. Their trunks are festooned with a tangle of lianas and canes. Underfoot is a mat of sodden leaves and all the fallen timber is like a wet and rotten sponge. Only too often, especially in the afternoon, the rain streams down, hour after hour. To get a fire going to cook some food or make tea under these conditions might seem impossible, but it can be done by those who know what to do.

In the rain forests of Queensland there is a tree whose wood burns when green. It is the ‘kerosene tree’ or ghittoe (Hal-fordia) whose heartwood is filled with minute specks of resin. It is identified by the absence of root buttresses, and by large, yellow-barked roots which twist about on the surface of the surrounding soil. The leaves are small, dark green, and resemble the fruit of a fig tree in outline.

A slab is split off the trunk of a ghittoe—a tough job, for it is one of the hardest timbers in the world and it cannot be done without an axe. Some of the saffron-yellow heartwood must be included. Little splinters of this heartwood are stuck in the ground in a circle with their tops touching, like the framework of an Indian tepee. Larger splinters are added, then pieces of wood the size of a pencil. The match is applied to the fine inner splinters through a gap left for the purpose.

It should be laid in a sheltered spot among the root buttresses of a big tree, as a little puff of wind will extinguish it when first lit. It is also necessary to stick the splinters firmly into the ground, because it will not burn if laid flat in the ordinary way. Although ghittoe wood is the best of them, there are other woods in the rain forests of Queensland, as well as in New Guinea, New Britain, and other tropical countries, which will burn green if the fire is laid in the way described.

They can be identified by asking natives to point them out, or by experimenting with splinters of the heartwood.

Another method in the Queensland rain forests is to look for the blue kauri pine, Agatbis palmerstonii. It can be distinguished from the brown kauri, Agathis robusta, because the trunk of the former is mottled with bluish patches, while the latter is a dull brown. When one of these trees is found, see if it has a broken limb—most kauris have one or two. Stand directly under the end of a broken branch and scrape away the leaves. Lumps of hard, glassy resin which have dripped from the stump will be found; they range in size from a walnut to a football. Even when wet, a chip of this gum will light with a single match and bum with a hot but smoky flame like that of rubber. A few chips will boil a billy of water.

In the rain forests of other tropical countries, members of the pine family of trees will be found which yield inflammable gum in the same way.

In the forests of southern Australia, look for trees such as the jarrah of Western Australia or the stringybark of the south and east of South Australia, Victoria, and New South Wales. Tear off strips of bark and rub the inner layer into bull’s wool. Wherever the blackboy, yacca, or grasstree grows, dry kindling can be obtained in wet weather by breaking off the dry, dead leaves which have been sheltered by the overhanging green ones. Porcupine grass (Triodia) burns green.

In very wet weather, little can be done with dead sticks gathered from the ground, as they are usually sodden. Break dead sticks off she-oaks or other casuarinas, from some of the wattles, particularly the blackwood, Acacia melanoxylon, or almost any of the gumtrees. If they are very wet, split them down the centre. The gidgee (Acacia cambagei) of the northwest of New South Wales and western Queensland, or any of the mulgas of the inland, are particularly good in this way.

Fire-lighting under adverse conditions is one of the most important of all things to the bushcraft student.

To bank up a fire in wet weather, so as to have hot coals for the morning, obtain some big banksia cones if possible. These were known as mangait (mahn-gah-eet) to the Aborigines of the south-west of Western Australia. Place some in the centre of the fire, fan until well alight, let them burn for a time, then cover completely with ashes and place a sheet of bark on the top to shield from the rain. In the morning, fan away the ashes and the mangaits will start to glow.

The same thing can be done with the chunky ends of hardwood logs. If gidgee wood is obtainable, it is merely necessary to put one end of a small log in the fire. It will smoulder away through the rest of the night without bursting into flame, burning only on the underside if it is raining heavily.

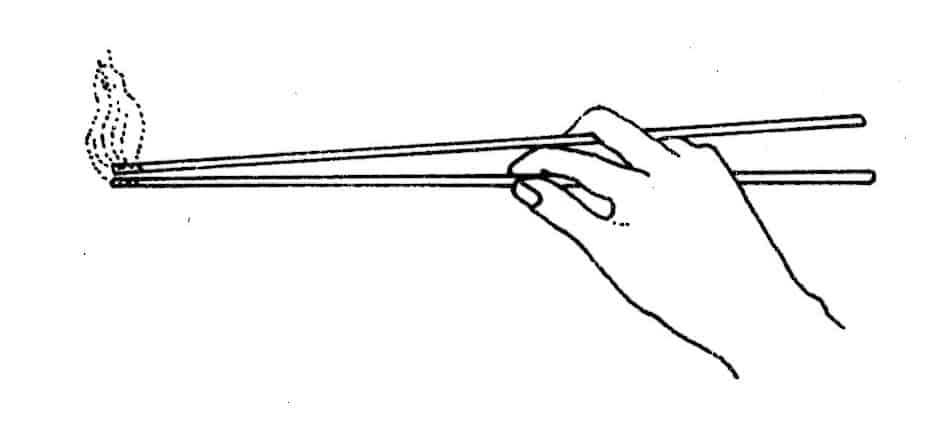

To carry fire from one spot to another some distance away, it is useless to try to do it with a single stick, unless it is a dry water-root from a gumtree or a stick of gidgee. Use two sticks with the burning ends together, as shown in the sketch. This is the Aboriginal method. It also helps to keep one warm when walking on a bitterly cold day. The sticks should be waved to and fro by swinging the arm while walking, to fan the burning ends. The drawback to it is the way in which the flying sparks burn holes in the clothing.

Carrying fire-sticks

I have seen Aborigines in central Australia with the skin of their upper arms, chests, and abdomens pitted with marks similar to smallpox scars, caused by the burns inflicted by sparks from their pairs of firesticks’.

From, ‘The Bushman’s Handbook’ by H.A. Lindsay. Harold Lindsay was a survival instructor with the Australian and American troops during World war 2.

See Also:

https://www.theultralighthiker.com/2015/05/26/how-to-light-a-fire-in-the-wet/

https://www.theultralighthiker.com/2020/02/27/tinder/

http://www.theultralighthiker.com/the-compleat-survival-guide/

http://www.theultralighthiker.com/how-to-light-a-fire-in-the-wet/

http://www.theultralighthiker.com/rope-dont-leave-home-without-it/

http://www.theultralighthiker.com/finding-your-way/

http://www.theultralighthiker.com/the-lie-of-the-land/

http://www.theultralighthiker.com/the-importance-of-a-roof/

http://www.theultralighthiker.com/carry-a-knife/

http://www.theultralighthiker.com/if-you-could-only-carry-two-things-in-the-bush-what-would-they-be/

http://www.theultralighthiker.com/ultralight-poncho-tent/

http://www.theultralighthiker.com/the-pocket-poncho-tent/

http://www.theultralighthiker.com/naismiths-rule/

http://www.theultralighthiker.com/weather-lore/

http://www.theultralighthiker.com/walking-the-line/

http://www.theultralighthiker.com/follow-your-nose/

http://www.theultralighthiker.com/how-long-till-sundown/

http://www.theultralighthiker.com/how-to-avoid-being-wet-cold-while-camping/