(or ‘journey cakes‘ as they once were known) also fried scones and maybe ‘bannock’ (from the Latin, ‘panis’ or ‘bread) if you hailed from Scotland. You can see that their (European) origin is quite ancient. They were once a basic food item. Folks took little else into the bush (by way of food) except for the main ingredients to make them – flour and some salt. They supplemented them with things caught or killed (fish and game) – as in this post.

Other than that, a tarp, blanket and axe to make a shelter and a fire with. A billy and a frying pan. Given that these items might be distributed amongst a number of people (along with the gun and the fishing line) I shouldn’t be surprised if this did not constitute a more ultralight mode of travel than most people undertake today, given especially that people might have been ‘up the bush’ for a month or more at a time on journeys in the past.

Shearers, shepherds and drovers especially used to make them. In C19th Australia these were folk who were ‘on the road’ (and mostly where there were no roads) for months at a time. Because of our vast distances (and being afoot) they were often weeks between supplies, as in this chorus (which I’m sure you recognise):

‘With my ragged old swag on my shoulder

And a billy quart-pot in my hand,

I tell you we’ll astonish the new chums

To see how we travel the land.’

I have always loved the old Australian folk songs: Wild Rover No More, Old Bullock Dray, Banks of the Condamine, Wild Colonial Boy, Moreton Bay, Flash Jack from Gundagai and the like. One of these old songs, ‘The Springtime It Brings on the Shearing’ collected by Overton in his ‘Wallaby Track’ collection in 1865 has the wonderful line, ‘after the shearing is over And the wool season’s all at an end, It is then that you’ll see those flash shearers Making johnny-cakes round in the bend‘.

You could check out this version of the song by an old (late) mate of mine from the 1960s, Gary Shearston, here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hc0YiR89vXw It is one of the best.

I like the holiday spirit of it. The sense that though the shearers are ‘flash’ (or ‘flush’ – with money) that their preferred abode is nonetheless just where you would have found that Australian icon the ‘Jolly Swagman’ of ‘Waltzin’ Matilda’ down ‘by a billabong’ or nearby the river’s bend (‘The river on its bars’ as ‘Clancy of the Overflow‘ expressed it).

‘the drover’s life has pleasures that the townsfolk never know.

And the bush hath friends to meet him, and their kindly voices greet him

In the murmur of the breezes and the river on its bars,

And he sees the vision splendid of the sunlit plains extended,

And at night the wond’rous glory of the everlasting stars.‘ – Aah!

Of course this is the best spot to camp. You are down out of the wind. Australia is awesomely flat. It rises (or falls) by only a few feet (on average) from one side of the vast continent to the other. For vast distances (hundreds, even thousands of miles) the gradient is less than an inch per mile! The wind blows almost constantly from the West more or less strongly. It is rarely less than 20 kph. In the summer the wind is a furnace’s breath. In the winter it has an icy chill. Spring and autumn are best.

Those Western rivers (of the Murray-Darling) which drain half the continent are very slow and meandering. There are a million such shady bends and many such billabongs where the river crosses the bend to make a new course. It is the easiest spot to get down to the water. There is often (usually) a sand bar, and of course the occasional floodwaters heap lots of handy firewood up nearby, but trees are always falling into the river or dropping their branches Australian trees are ‘self-pruning’, so beware. Don’t camp under a large tree.

The Western rivers of Vic, NSW and Qld (the Murray-Darling Basin) are still today a great way to see the real Australia. Mostly the river margins are public land and so can be traveled (by foot or canoe) with great freedom. Of course any scattered towns are strung out along the rivers like pearls. They still provide innumerable camping opportunities especially away from roads. River heights and recommendations here: http://www.waterwaysguide.org.au/AboutUs & https://www.adventurepro.com.au/paddleaustralia/ & https://paddle.org.au/recreation/where-to-paddle/

The rivers are alive with fresh fish, eels and crayfish of several different kinds – yabbies and ghost shrimp mainly, but also ‘Murray Crays’ – in any case some of the tastiest tucker you could wish for. And naturally countless wild ducks. When I was a kid the country was also alive with rabbits, sometimes almost literally. I have seen whole paddocks which seemed to be just a moving blur of their tawny fur. Not so many these days, but still worth your while to carry a gun to supplement the pot with. All good eating, and a pleasant accompaniment to your ‘cakes’.

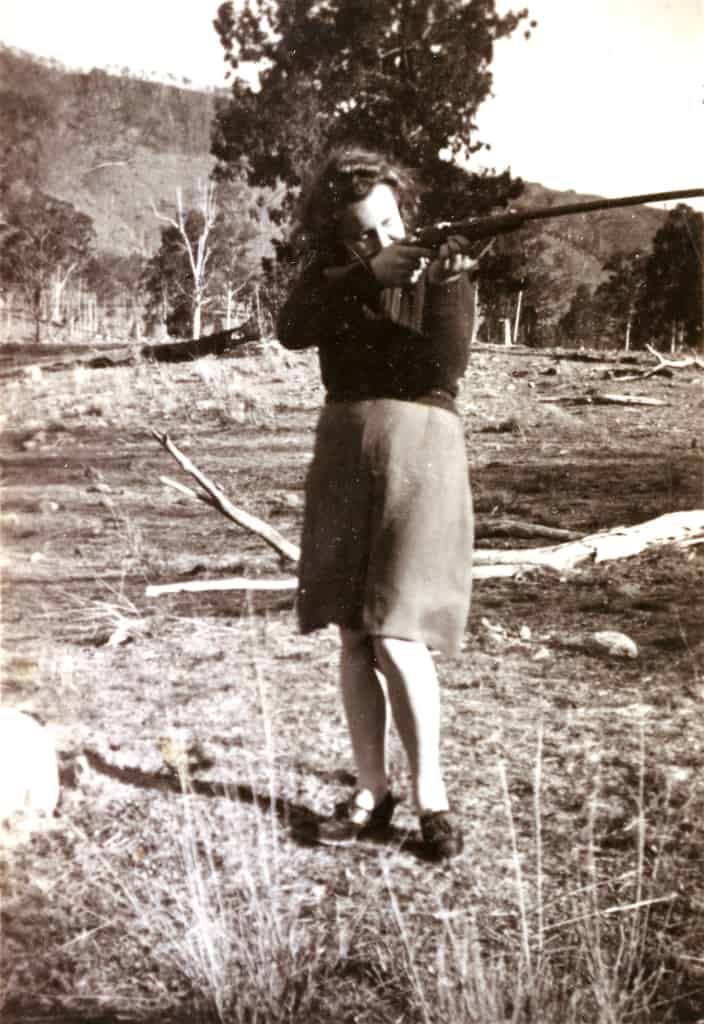

Marie Jones c1945 Great Dividing Range securing a rabbit for the pot.

The ‘ghost shrimp’ require a hoop net covered with fine material. They are normally invisible against the bottom – even in clear streams (which the Western rivers are not – take a filter). Practically anything will attract them (even a bar of ‘Velvet’ soap)! You will be astonished at just how many there are – though they are small (2-3″ usually). Still it doesn’t take long to get a feed. Just bring them to the boil in your billy. They colour when they are ready < a minute will be enough). You can peel them if you like, but they are fine eaten whole if you don’t mind crunchy. Yabbies and crays will need peeling.

Many of the rivers are now alive with European carp which are not great eating from muddy water. Their (preferably rotting) flesh is great bait for crayfish of all sorts though. The yellow (and silver) perch – and of course the ‘Murray’ cod are great eating, as are freshwater eels. You will not go hungry along the Western rivers. Apart from wild ducks (which can be legally taken – licence conditions apply) the thousands of miles long fringe of bush along the rivers is home to an astonishing array of creatures: hundreds of different bird species (especially obvious are the brightly coloured parrots and finches), many kinds of reptiles (nothing that can eat you – but there are many poisonous snakes, so take care) and amphibians, lots of marsupials (the grey kangaroos as the most numerous), but there are many possums and smaller creatures too. As you ‘travel the land’ of this vast river basin you will always have several wild creatures in sight – and that is only in daylight. remember most of Australia’s animals are nocturnal or at least crepuscular.

The Murray alone is 2500 km long and the Darling 1500 km. There are over a dozen tributary rivers flowing into the Darling alone. Some of the Murray-Darling tributaries are huge themselves: the Lachlan and Murrumbidgee are each 1500 km long!

If you are traveling inland between Melbourne and Sydney or Brisbane it is well worth your while to go out of your way and detour from Cowra to Forbes along the magnificent Lachlan Valley Way which parallels the Lachlan River for nearly 100 km. Here you will see many billabongs and some splendid examples of the remnant forest I have been talking about. In many places you can simply drive off the road and across to the river, sometimes a kilometre away. There are many great camping spots.

My parents were itinerant beekeepers in Western NSW chasing the honey flow for months at a time along the remnant forests which skirt the Western rivers. We camped along those waterways all through the 1940s and 50s but they are little changed today. My mother often made ‘Johnny Cakes’ for us by the banks of a river on a trusty much-repaired Primus stove. Every night we slept under canvas on an army cot wrapped in our woolen blankets, lulled to sleep by the chorus of frogs, the chitter of possums and the splash of fish jumping in the river…and always, ‘the wond’rous glory of the everlasting stars’ – as Clancy phrased it. Under that clear, dry air there are more stars than you will see anywhere else on earth!

Lawrence Jones c1945 with 1926 Chev truck . Great Dividing Range. Note honey tins and hound Felix.

In the C19th (especially) the Western Rivers became ‘highways’ for itinerant workers (such as shearers, shepherds, drovers etc) and the river bends became way-stations. My great grandfather, George Harvey was a carter (as his father before him) bringing wool down from the great outback stations to the (then) important river port of Morpeth on the Hunter River upstream from Newcastle. They were camped one night outside Uralla New England NSW with such a load when the menfolk decided to go into town to the pub at night for a few drinks. My great grandmother Margaret and a baby (maybe my grandmother Rose) were camped under the bullock dray. During the night she heard men’s voices approaching and the baby decided to cry. She then heard a man’s voice say “Come away there is a woman’ and they faded into the night. This would have apparently been Starlight or Thunderbolt the bush rangers. One of them was well known for his delicacy towards women.

You can imagine some of the camps becoming quite permanent eg with bark huts popping up amongst the river red gums. Much construction was done with what would be considered rubbish today: earth, twigs, bark etc. Rabbit skins for example were a useful resource (likewise wool). Fencing wire (and netting) found a thousand uses from toasting forks to building fasteners (See: https://www.theultralighthiker.com/2018/09/08/the-spanish-windlass/). The netting was an important component of fish traps which ensured a ready supply of fresh fish. Unfortunately some platypus and turtles drowned – this does not happen if a sufficient part of the trap is left above water and checked regularly. Empty kerosene drums were flattened for all sorts of uses (think skillets and even building cladding and roofing). Used newspapers were ‘painted with flour and water to create (entertaining) dividing walls. Families often grew up in such huts. I know I spent my early years in a house with an ‘ground’ floor – as we used to call it when the earth was the floor. You can still see this today at Harry Smith’s Hut at Eaglevale on the Wonnangatta. There would be little archaeological evidence today of such important camps.

Johnny Cakes are just a version of damper except that they are fried rather than baked. If you don’t have a frying pan you can just wrap the dough around a stick and bake it over the coals turning and turning it until it is brown and crisp on the outside, yet still doughy on the inside – or you can filch a length of netting from a farmer’s old fence or a stray sheet of corrugated iron will also serve as a griddle. Or you can acquire a frypan! I prefer to use a bit of dripping or tallow (mutton fat) to fry them with as it has the highest melting point (40C) of all fats. It is also tasty. Oil is too hard to transport without the risk of leaks and having packs and clothes thoroughly messed up.

I used to have lots of recipes in my head for them, as I made them all the time, but I guess that’s over twenty years ago now, and I never wrote them down. My mate Woody reckoned the best mix was to just add flour to a can of beer until you had a stiff dough, and then fry that. Tasty I agree but seems like a waste of a cold tinny – and I usually don’t have one in my pack anyway. There is some sound advice there though. If you mix this way, slowly and carefully you will get to the point where the dough is no longer sticky and it all comes off the surface you are ‘working’ it on and your hands and fingers also become perfectly clean without washing. Then it is time to cook.

Recipes: The oldest plainest recipe was to use a 1 lb (500 gram) packet of self raising flour to 1 teaspoon of salt. Mix slowly with about 3/4 of a cup of water – but remember the earlier advice: add the water slowly until you have a very stiff dough which removes all the sticky from your hands and work surface. Make into cakes about 3-4″ wide and 1/2-3/4″ thick and ‘fry’ slowly on low heat. Turn when golden on one side.

I would add to that some powered milk (a table spoon?), a teaspoon of sugar, a couple of teaspoons (perhaps) of desiccated coconut and a couple of teaspoons of slivered almonds. Of course you can add anything you like to make them a bit tastier (sultanas or raisins for example). It can be a good idea also to work some ( a few teaspoons) of the dripping into the cake mixture before you fry them.

On many long journeys in the past I have made them up to go with my evening meal and held a few aside to eat with some condiment (jam, peanut butter, etc) for my lunch. I must be getting old (and I am trying to cut down on the carbs); I am finding such chores a bit wearisome these days. That being said, having written about the damned things I really have a hankering to make some now! Cheers.

‘Oh, the springtime it brings on the shearing,

And it’s then that you’ll see them in droves,

To the west country stations all steering,

A-seeking a job off the coves.

Chorus: With my ragged old swag on my shoulder

And a billy quart-pot in my hand,

I tell you we’ll astonish the new chums

To see how we travel the land.’

PS: Of course, as you know we have been sheep farmers for over thirty years, so we have more than a passing acquaintance with shearers and shearer’s songs – and food!

Talking of Johnny Cakes and billabongs reminds me of our national song:

Deconstructing Waltzing Matilda, Australia’s Favourite Song

Waltzing Matilda is an Australian icon. It is quite likely that more Australians know the words to this song than even their national anthem. There is probably no other song that is more easily recognised by a populace: young or old: native or a newly arrived immigrant.

The lyrics to Waltzing Matilda were (allegedly) written in 1895 by Banjo Paterson, an Australian bush poet, while holidaying on a huge cattle and sheep station (ranch) in the Australian Outback. He was inspired by a tune he heard being played by Christina Macpherson the daughter of the owner of the property.

Banjo and Christina worked together composing the song. Whether they also got it away is left to your imagination. She set the music for Waltzing Matilda. The song was an instant hit. The words were written to a tune played on a zither or autoharp by 31‑year‑old Christina, one of the family members at the station. 31? Old for such high jinks!

Macpherson had heard the tune ‘The Craigielee March’ played by a military band while attending the Warrnambool steeplechase horse racing in Victoria in April 1894, and played it back by ear at Dagworth. Paterson decided that the music would be a good piece to set lyrics to, and produced the original version during the rest of his stay at the station and in Winton.

As with so many icons of the Left, there is a degree of dishonesty at its heart. For example, the tune was stolen: The march was based on the Scottish Celtic folk tune ‘Thou Bonnie Wood of Craigielea’, written by Robert Tannahill and first published in 1806, with James Barr composing the music in 1818. In the early 1890s it was arranged as the ‘The Craigielee’ march music for brass band by Thomas Bulch.

This tune, in turn, was possibly based on the old melody of ‘Go to the Devil and Shake Yourself’ (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xO1DPWLumvw), composed by John Field (1782–1837) sometime before 1812. Banjo’s song was first recorded by John Collinson in 1926. You can listen to it here: http://aso.gov.au/titles/music/waltzing-matilda/clip1/ I think I prefer the original title, ‘Go to the Devil and Shake Yourself’!

Of course Paterson composed the song in what was to be the birthplace of Australia’s Left (Australian Labor Party = Barcaldine) just after the great ‘Shearer’s Strike’ of 1891 (itself a consequence more of the 1890’s (climate change) drought than anything else, and the founding of the unsuccessful ‘New Australia’ in Paraguay (by the disgruntled leftist insurgents 1892).

All these things are connected, and connected to the Australian leftist (ortho) doxy! One day their history will be written, but not be me! In 1890 Bourke was a centre of ‘culture’ (if you can call anything the left touches ‘culture’), had a grand opera house, was a centre of ‘civilisation’ and a magnet for the literati. It was no accident Paterson was there.

Today it is a hell hole (after a century of leftist social experimentation) with the highest crime rate of anywhere on the planet, for example. Interesting aside: In the Western Lands Lease country (West of the Darling) in the 1880s you could milk a cow on four acres. There were substantial towns all over the place and 100,000 folk lived there. The great drought of the 1890s (which never ended) caused all those people to move and all their settlements to be abandoned. Climate change!

The ‘New Australia’ movement wanted to secede and form their own socialist paradise there. It had to be abandoned as a result of the 1890s drought (that’s why they went to Paraguay https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Australia) and never recovered. No-one at all lives there today! I suspect a leftist future is no different from a leftist past!

The socialist ‘experiment in Paraguay (like all such elsewhere) did not work out either, and was eventually abandoned – the descendants of those settlers were accepted as Australians by the Whitlam Government in the 1970s when they returned to Australia. Caroline Jones made a doco (‘And Their Ghosts May Be Heard’) about it (which was excellent). You can buy it here: http://shop.nfsa.gov.au/and-their-ghosts-may-be-heard

First read the song Waltzing Matilda (below) again , then I will begin to ‘decontruct’ it for you:

Waltzing Matilda, Lyrics to Song

1Once a jolly swagman camped by a billabong

2Under the shade of a coolibah tree

3And he sang as he watched and waited ’til his billy boiled

4Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me?

5Waltzing Matilda, Waltzing Matilda

6Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me

7And he sang as he watched and waited ’til his billy boiled

8Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me?

9Along came a jumbuck to drink at the billabong

10Up jumped the swagman and grabbed him with glee

11And he sang as he stowed that jumbuck in his tucker bag

12You’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me.

13Waltzing Matilda, Waltzing Matilda

14Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me

15And he sang as he watched and waited ’til his billy boiled

16Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me?

17Up rode the squatter, mounted on his thoroughbred

18Down came the troopers, one, two, three

19Whose is that jumbuck you’ve got in your tucker bag?

20You’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me.

21Waltzing Matilda, Waltzing Matilda

22Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me

23And he sang as he watched and waited ’til his billy boiled

24Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me?

25Up jumped the swagman, leapt into the billabong,

26You’ll never catch me alive, said he

27And his ghost may be heard as you pass by the billabong

28Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me.

29Waltzing Matilda, Waltzing Matilda

30Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me

31And he sang as he watched and waited ’til his billy boiled

32Who’ll come a-waltzing, Matilda, with me?

Just some key words: First ‘camped’ (Line 1) rather than ‘trespassed’. This innocuous word sets the scene for who is in the right and who in the wrong in this interchange of ideas and clash of social classes. The swagman is innocently ‘camping’ amid a benevolent nature which will provide him with all its largesse (food, drink peace) as his ‘right’. The tranquillity and ‘appropriateness’ of the scene is emphasized over and over again by the choice of words ‘waltzing’ and ‘singing’ for example (Lines 11,12,13,14,15,16!).

There is no indication that he is a ruffian who has no business being where he is. In reality the swagman is a shiftless idle derelict, illegally trespassing on someone else’s private property which the owner has paid good money for and spent considerable effort and work building up, eg creating mobs of (highly edible) sheep, which the swagman wantonly kills and steals.

The ‘class’ difference between the protagonists (and the role of the Government in reinforcing this class system) is emphasized by the choice of word to describe them their conveyances and possessions. The swagman is on foot (‘waltzing) whereas the owner (described disphemistically) as a ‘squatter’ (as if he had no right to the land -though he had actually paid for it!) is ‘mounted’ (to stress his ‘

High falutin’ nature, and not just on any common nag (it would in reality have been a ‘whaler’) but on a ‘thoroughbred’ (which would in fact have been little use for mustering sheep – it would break its legs!) His actions are backed up by the full force of the establishment and the law by the presence of not just one but by a whole bevy of gendarmes (three) so that at the outset the ‘poor’ swagman is outnumbered (four to one) by the onerous forces of capital and the law – O, the injustice of it all!

Of course the poem was written in response to the Great Shearer’s Strike (it became almost a civil war) and led to many gaolings and deaths, and the burning of many shearing sheds – and also to the founding of the ‘New Australia’ colony in Paraguay and incidentally to the founding of the Labor Party, not far from where it was written – by just such leftists as Paterson.

In those days Bourke was a centre of culture. Many people wanted to form a socialist republic West of the Darling where 100,000 people dwelt then (but no-one does today- after the drought of 1890 failed to go away – climate change!) Today Bourke has the highest crime rate in the world!

Let’s look at how that crime is dealt with: The ‘jumbuck’ (‘sheep’ = Line 9) is obviously innocently coming to the stream for its evening drink when the swagman ‘grabs’ him and ‘stows’ him. The violence of this encounter is glossed over and the swagman places the remains of the sheep in his food bag as if it were his own property.

There is no hint in the song though of ‘blood upon the wattle’. There is no indication even that the action was ‘unkind’. The sheep might almost later on extricate itself from the offending bag after having had a peaceful nap, and saunter on its way as if the whole episode had been a friendly jape! Performed after all, with ‘glee’.

I’m not sure however if the wether appreciated the jest! He is a bloody mess of meat after all, hacked to pieces. It is astonishing to what an extent the passivity of the crime is glossed over. The swagman just ‘watches and waits’; it is the squatter and his troopers who are the actors. They ‘ride up’ and ‘come down’, etc.

The squatter at least comes straight to the point, ‘Whose is that jumbuck’? He says. Every event in Australia’s history revolves around how you answer this question. We all are supposed to ‘know’ surely by now (the Labor Party and the Trade Unions have told us often enough) that the ‘bosses’ have (mis) appropriated all the world’s wealth for their own nefarious purposes, holding the rest of us in an impecunious subjugation which will not even end with our deaths.

‘You’ll never catch me alive’ sings the swagman and ‘jumps into the billabong.’ He almost certainly needed a good bath anyway having been an indigent derelict sleeping rough for some time and no doubt carefully boiling methylated spirits (or the ‘White Lady – I know you imagined ‘tea’ – such innocence) in that billy anyway, a foul habit which can often also lead to incontinence and madness – which it clearly has in this case!

It was clearly quite mad to drown yourself simply over the theft of some mutton anyway, a crime which would most likely only have met with a small fine in those days. If this event is supposed to have taken place before Samuel Mort invented refrigerated transport (c1883 and therefore likely – Now Elders incidentally), then you should know that meat was practically free up until then as the only usable products of the grazing industry were tallow (fat), hides and wool as anyone who has played the board game ‘Squatter’, an Australian version of ‘Monopoly’ ought to know.

Meat was simply a waste product. At one time for example they used to tip up to 4 million sheep carcasses into the Murray at Echuca annually (after rendering). The smell (and environmental consequences) are hard to imagine. One thing though; it did lead to the development of the largest Murray Cod in history (bigger than a man!), and indeed to an inland fisheries industry, now sadly defunct!

You will note that the cops (troopers) do nothing. Just like cops of every age, they are just in it for the take, eg their fat horses. They do nothing to prevent crime or to solve it.

I also like the morsel of moral advice that you should ‘pass by this billabong’. Its pollution by dead swagmen and sheep is bad enough. I think there is also the suggestion that ‘you’ should eschew a like fate. Whether this means you should desist from rustling, drinking meths, bathing, having anything to do with the police or etc is left to your own imagination – as it should be!

The constant refrain ‘Who’ll’? and its answering chorus, ‘You’ll’ is just too obvious to require explanation. If you have been sucked in by leftist gibberish, no doubt you are totally ignorant and might as well be off ‘waltzing matilda’ with the fairies or lying somewhere (dare I say ‘unlamented’?) on the bottom of some Billabong or other suitable receptacle for the disposal of dead bodies!

The swagman will have his revenge. We are doomed to be haunted by his ghost – just as we are haunted by the ghosts of Whitlam and Keating! Wait a moment! Keating is not dead. He just always looks dead. His is the undead hand of capitalism! Or socialism. Well, something like that.

See Also:

https://www.theultralighthiker.com/2017/07/29/a-hiking-food-compendium/

https://www.theultralighthiker.com/2017/08/07/humping-your-bluey/

https://www.theultralighthiker.com/2018/06/02/mattresses-i-have-known/

https://www.theultralighthiker.com/2018/09/08/the-spanish-windlass/

https://www.theultralighthiker.com/2017/07/01/out-of-the-frying-pan/

https://www.theultralighthiker.com/2019/06/23/the-pack-rifle/